"The Bible affirms that on earth the unrighteous experience some of God's blessings...These blessings are not the same as salvation...So we have a paradox. People without God experience many of God's blessings. John says that Christ, 'the true light... gives light to every man.'" (John 1:9)--Ajith Fernando, Crucial Questions About Hell

Welcome

Sonja and Irene had barely been in my dorm room a minute before they attempted to raid my mini-fridge. This is how I know my friends are comfortable here. “Looking for the care package my mom and dad sent?” I asked, holding up a cardboard box. I fished out two foil-wrapped brownies and threw one at each friend.

While we munched, Sonja said, “Usually just my mom sends me care packages.”

“Book from my dad, food from my mom,” I said between bites.

“What book?”

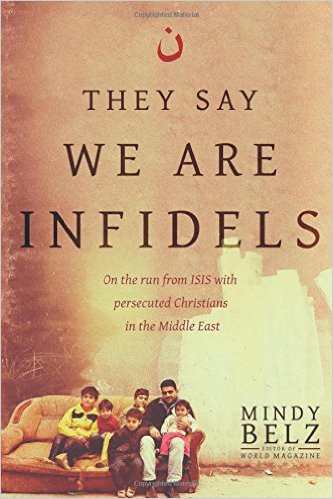

“It's about something he wanted me to consider,” I evaded. “Kind of interesting, though.”

Then I quickly shifted my gaze from Sonja to Irene. Irene had been staring at the snow outside, a late-spring sugar snow. Her face was reflected dimly in the glass of the window, eyes solemn to match the cast of the sky. The blue-white glare of the snowy landscape was too bright.

I thought silently, “It’s as if the sun has come dangerously close to the earth.”

Apparently, Irene had noticed me staring off into space.

“Whatcha thinking, Vivian?” she asked.

“How I would describe this scene in a story,” I admitted.

“You and your stories--you're always so enslaved to your writing,” said Sonja.

“What are you writing, anyway?” she asked, sidling up to my straight-backed desk chair.

“Nosey!” I giggled, starting to close my sleek laptop.

“Okay, okay, I won’t read it.”

“Is it the one you showed me--the disturbing story about a little girl?” asked Irene. I nodded. “If it’s disturbing, maybe I shouldn’t read it then.” said Sonja, mischief dancing in her dark eyes.

I set my trap carefully: “Maybe I shouldn't let you. You know what they say about writing. What if it reveals all kinds of secrets about me and my childhood?”

“Actually, Sonja, it’s more that it's kind of intense,” I said, looking straight at her. “Some people might say it's morbid.”

“Now I want to see.” she replied.

I opened the laptop and tapped a few keys.

Sonja said, “I'll read it out loud, since you both know what's in it.”

And she began to read.

Dreams and Visions

A little girl and her mother sit side-by-side in the living room. Slanting Texas sunlight slides in between the blinds, marking out stripes on the floor like the intervals of a timeline. The girl, about seven-years-old, watches dust motes drift in the air. And that is what she will always remember that afternoon: “It was so tranquil at first.”

"Let's read the one about stars," says the mother, pulling a book off a stack on the floor. Its cover looks like a shining color photograph of outer space. Luminous nests of stars twinkle out from behind the clear plastic dust jacket: this one holds good promise. It might even be a new friend.

The child reads.

Soon, the mother is lulled towards sleep by her daughter's voice, clear and rhythmic and steady. The child looks over at her.

“Do you ever think about space, Mom?”

The mother snaps awake, thinks for a second, and then answers. “Not much lately,” she admits.

After a pause and a sip of the dregs of her coffee, she asks, “What do you think about space, little one?”

“About how it's so big, like you can run and run practically forever and never get to the end.”

The mother looks amused, “You actually enjoy thinking about this stuff.”

The girl looks surprised, “Of course! It's like dancing with the genie.”

“You mean the genie from Aladdin?”

“Yeah... like you're swept away. And by something stronger than you! Because you get to imagine something so big that you never would have imagined it before! And then you do the next thing!”

“Swept away in a dance by an otherworldly being,” says the mother, more to herself than to the child. “I like it. And the genie in Disney’s Aladdin was such a cheerful version,” she adds, wiggling her toes out of her blue flip-flops.

The mother looks at her daughter again. “What is your favorite thing from these books?”

Immediately: “Neutron stars. They weigh SO much. It says that just a drop of one would be more than a BILLION TONS on Earth. It would CRUSH you!”

“And how huge the ones called red giants get... like Beetle-juice.”

“I don't know - that sounds pretty scary,” the mother says.

She tastes a sip of coffee and waits.

“But nobody can live on Jupiter or Beetle-juice. So nobody would go there!”

The mother chuckles, and they resume their reading.

But then the child discovers something she did not expect. The book tells her that not only distant Betelgeuse—but our own particular star, the sun, will become a red giant. It will swell to an enormous size, perhaps swallowing the earth. An inhabited world engulfed in a ball of red fire.

The child turns her large dark eyes to her mother in distress. “Will this really happen? Will the earth and all that is in it really be destroyed?”

Sonja paused and turned to me, her face lit up by the digital glow of the screen.

“She sounds a little like my sister. I could imagine her getting worked up over something like that. So frustrating.”

Irene said, “Sounds like one or two of the kids I have in Sunday School!”

Sonja smiled sympathetically and then went back to reading.

Her mother answers the child as seems good to her: “Oh, five billion years is so far away that...” The mother gestures in the air, but finds it futile to mark out such a span of time. She begins again: “That won't happen until after you have died and after your children have died and your children's children and their children and so on and so on. It's so far away.”

The mother hugs the little child with such serious questions. “Don't worry about it.” But her answer created a whole new set of questions for the little girl, who never thought about the children she might have one day or their children or their children's children.

Or about dying.

Sonja looked over at me to say, “Well, that is intense. Now, where's the punchline?”

I pointed, and she began again.

That night, at bedtime, the child says to her father, “I have a question.” He listens. “What about when I die?”

Sonja said, “I see.” and got really quiet. She finished reading my story in silence and then looked up.

She repeated the last sentence: “The little child goes to sleep.”

Revelation

“So a little girl, at seven years old, decides that if she does great things, she will be able to live on in others' memories,” said Irene. “And she thinks that works.“

But then Sonja turned to her: “Well, I don't see how it's disturbing.”

“I was bothered by the fact that I couldn't go to the child and help her,” said Irene.

I looked straight at her and said, “Irene. You have helped her, and you do help her.”

Irene gave me her “You are a weirdo” look and I could have laughed, but instead, said softly, “I am the child.”

“Oh.” Now she looked delighted.

Sonja went on talking, somewhat obliviously: “It's kind of sweet and comforting. Like... her parents love her, and the little girl feels safe.”

“Yes. Her parents love her.”

Irene thought about that for a second, eyes searching this way and that. Then she spoke: “But the conclusion the characters in the story come to... is that if she does deeds worthy of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, then she will be remembered long after she dies.”

“In the minds of others.” intoned Sonja, without a trace of irony.

“But that's not supposed to be a Christian hope, is it?” asked Irene, looking to me for assent.

“It's totally a worldly hope, Irene!” I answered her.

“And it's ummm - you know - a little bit of a burden for a five year-old child.”

“Seven.” said Sonja.

“Oh, yeah. Right. Seven.”

“So then how is it a Christian story?” asked Irene.

“It's about lostness!”

Now they both stared at me dumbly.

“It's so easy to forget what 'lostness' is like. And what it feels like! Lostness often doesn't feel like being lost!”

Sonja motioned to a spot in the middle of the faded blue carpet: “That is now your soapbox. Go... take ownership of it.”

I walked over there, smoothed down some loops of the fraying rug, and continued to speak.

“We are tempted to quickly dismiss some of the concerns of people who do not follow Christ. As Christians, we tell ourselves we 'know we don't need to worry about those problems.' But maybe these concerns are more like our own concerns than unlike them.”

“Like the world being destroyed by fire.” said Irene.

Then Sonja turned to Irene: “You know, this reminds me of that one book we've been reading. It was talking about how pride really hampers witnessing.” And that was when I knew I had them. No telling how long this would last... but, for now, I had them.