To Welcome the Pilgrim Home

by Trisha Williams

“I hate this book.”

“Why do you hate it?”

“I hate it because it’s so true it makes me uncomfortable. I see myself on every page. Well, not on every page. Just when Christian messes up and acts stupid.”

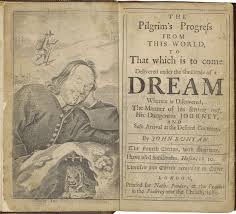

The book in question was Pilgrim’s Progress, an allegory rebel preacher John Bunyan wrote from a prison cell in Bedford, England, in 1678. The truth-teller happened to be my fifteen-year-old nephew speaking to me, his history teacher, in class in front of nineteen of his peers.

Lots of questions ran through my head. Did my nephew just say he hates the greatest piece of English religious literature, outside of the King James Version of the Bible, ever written? He hates the book that’s been translated into 200 different languages and has never gone out of print? He hates the book that the famous literary critic Samuel Johnson praised by saying “the most cultivated man cannot find anything to praise more highly, and the child knows nothing more amusing”?

And then his words sunk in. My nephew just admitted that his conscience had been pricked! Bunyan would be so pleased! I told my nephew and the whole class:

“I’m glad it bothered you. Keep thinking about why.”

John Newton wrote in his preface to Pilgrim’s Progress in 1776:

If you are indeed asking the way to Zion with your face thitherward, I bid you good speed. Behold an open door is set before you, which none can shut. Yet prepare to endure hardship, for the way lies through many tribulations. There are hills and valleys to be passed, lions and dragons to be met with, but the Lord of the hill will guide and guard his people. “Put on the whole armor of God, fight the good fight of faith.” Beware of the Flatterer. Beware of the Enchanted Ground. See the Land of Beulah, yea, the city of Jerusalem itself is before you:

There Jesus the forerunner waits.

To welcome travelers home.

I was thinking about Newton’s words on November 7, 2015, while observing the men and women sitting in a room at College Church. They were learning about and contemplating doing something radical, something brave, something that will probably require great sacrifice, many tears, late nights, early mornings, “hardships, lions and dragons, and fights.” They were learning about Safe Families and contemplating welcoming the traveler home through radical hospitality.

Since 2002, Safe Families is on a mission to reengage the Body of Christ to once again be known for their active love specifically through hospitality to children of families who are in crisis. Safe Families seeks to helps both parents and children in such a way that children who have been placed out into host families will one day be restored to their parents. Church historian Tertullian said that the early church was branded by “our care for the helpless, our practice of loving kindness that brands us in the eyes of many of our opponents.” Is loving kindness and radical hospitality to the helpless now what the church is known for?

Though I have certainly seen pockets and enclaves and glimmers of this love all around the world, I know the church is not currently branded by this in the eyes of the watching world. We are often today known for what we are against and not what we are for.

God is for the weak, the helpless, the family, the poor, the vulnerable, the sick and the big and little people in crisis. He is for these people because he is truth, he is life, he is holy, he is just, and he is the very definition of love.

As far as I can tell the church in the United States started abandoning the types of people God loves in the late 1800s. Things took a turn for the worse during the Great Depression when the Social Security Act became law. By this point, the church was absent from the conversation of who would care for children and families in crisis. By the 1950s, orphan and foster care were entirely the responsibility of the government and continue to be so today.

If the church stays content to let the government care for our neighbors who are in crisis, doesn’t this mean that the church that Christ died for is failing in its job to care for the widows and orphans and to seek justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with God on the pilgrimage to heaven? Are we loving our neighbors (who might be homeless, jobless, trapped by addiction or plagued by mental illness) as we love ourselves when we call a government agency instead of opening our doors or calling our local church to see how we can help these men, women and children?

As much as I love and am encouraged and challenged by Bunyan’s allegory of Christian’s pilgrimage to the Celestial Kingdom, I do wonder why it seems that Christian is so alone on his journey. He leaves his wife and children in the City of Destruction and when the character Charity, one of the four mistresses of the Palace Beautiful, questions him as to why he left his family behind, Christian begins to weep. The other problem I have with the allegory is that though there are individuals who would comprise members of the church (Evangelist, Help, The Interpreter, Faithful, and Hopeful) a symbolic representative of the entire universal church is absent from the story. Both of these problems can be understood when you realize that John Bunyan was writing alone from a prison cell having been kicked out of the state church and separated from his family.

With her husband in jail for twelve years Bunyan’s wife, Elizabeth, was left to care for their six children on her own. This was a family in crisis. With a father in prison, no income and looming homelessness, most likely if this had happened today somebody would call the Department of Child and Family Services and a social worker would come and undoubtedly place the six children in foster care and Elizabeth would be left to fend for herself. But this happened in the late 1600s, and followers of Jesus stepped up, and for 12 years provided respite care, food, and money to pay bills for the Bunyan family. This was radical love. This is the same radical love that Christians are called to engage in today.

November is a month to celebrate family and to give thanks. Perhaps this year as you set the table for Thanksgiving dinner and perhaps recall the original pilgrims at Plymouth Plantation giving thanks alongside the Wampanoag Indians who had shown them incredible hospitality during their first year wracked with crisis in the New World, you might find yourself adding one more plate to show hospitality to a young stranger in need of care.

Jesus said to his disciples who wanted to know who was greatest in the kingdom of heaven: “Truly, I say to you, unless you turn and become like children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven. Whoever humbles himself like this child is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven. Whoever receives one such child in my name receives me.” What an incredible promise! What an incredible challenge.